Board in the Library, Part One

An Introduction to Designer Board Games

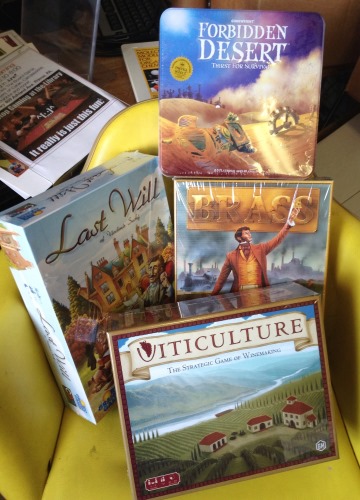

This article is the first in a six-part series on board game programming in public libraries, from John Pappas, the Branch Manager at the Bensalem Branch of the Bucks County Free Library System. (Read Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four | Part Five | Part Six). See also webinars with John on boardgames: The Golden Age of Gaming: Board Games for Grown-ups and Whose Turn Is It, Anyway? Online Board Gaming and Libraries.

An Introduction

An Introduction

In a world of apps, massive online games, connected mobile devices, and shiny new game consoles, the physicality and social aspect of gaming begins to wane. All of this despite most online gaming being touted as, well, social. Players become more detached from play and removed from the physical medium as well as from other people.

Board games provide a way out of this desocialization by providing a physical, manipulable medium for patrons to interact, grow and explore in a physical space (hopefully within a library). In an attempt to connect with patrons who desire diverse gaming experiences - game experiences which engage their imagination, spur critical thought, and exist in a physical rather than digital realm - the Primos Branch of the Upper Darby Free Public Library piloted three separate gaming groups in the Summer of 2013: a weekly, intergenerational "Tabletop Gaming at the Library" program; a monthly "Game Designer’s Guild," and; a monthly "Golden Gamers" which focused on gamers aged 65 and over.

While the idea of video game events in the library has become popular to the point of being innocuous and intergenerational with the advent of the Wii and mobile gaming; the growth of designer board games is not as well known or appreciated by the library world. The designation of these games as "designer," "hobbyist," "modern" or "niche" may be daunting and deter libraries from incorporating these board games into existing gaming programs. Incidentally, the designation of "designer" in designer board games is due to nothing more than the tendency to place the name of the designer directly on the front of the game's box. Similar to the author of a book or director of a motion picture, a game designer can go through phases, create duds, be considered a one hit wonder, or be prolific and well-known outside of their preferred format.

This article is an introduction to the six-part series; elucidating the mechanics, themes, and interactions inherent in designer board games and provide a base of knowledge appropriate to the medium which will provide librarians and library staff the inspiration to play, teach, promote and even create designer board games. Likely, before all of that, designer board games need to be defined next to their older and, frankly, sometimes duller, older sibling - the mass-market board game.

Woah! Slow down there, bud.

Yes, Interrupting Heading? How can I help you?

Where else can I learn about board games now?

Well, yes -

Your Friendly Local Game Store is the best place to start and it may be a comic book store, a store focusing on miniatures and Magic: The Gathering, or a store that focuses on board and family games. Either way, there is a good chance they host public board game events. It is a good place to lurk, observe, ask questions, play games, and explore the space. Part of the rationale behind starting my library group was the displeasure some patrons expressed at gaming groups (or lack of them) at their neighborhood FLGS. Either the demographics were not aligned with their comfort, the games were unfamiliar, or the atmosphere was intimidating. My impetus in starting our suite of board game events was to provide an accessible, friendly and appropriate board gaming space for all ages and experience levels.

If person-to-person interaction is not your thing then I recommend reading two books. First is Libraries Got Game: Aligned Learning through Modern Board Games by Brian Mayer and Christopher Harris. While focusing on school libraries, it provides wonderful fodder for convincing staff and generating buy-in (a topic I will explore in this series) as well as a list of potential games to start a collection (a topic I will also explore in this series). Then check out Dr. Scot Nicholson's Everyone Plays at the Library for a good introduction on play and how it can be incorporated into the library space.

Lastly, anyone interested in designer board games needs to visit Boargamegeek.com and become intimately familiar with the "Hotness" list (a list of what is currently visited most on the site) as well as the list of mechanism and themes as well as lists of the most popular strategy, family, thematic, and war games. The site, while bulky and not particularly accessible, is the most comprehensive and detailed resource for board games.

What makes these games so different from the games I grew up playing?

While there may be a number of similarities between designer board games and the games you are familiar playing, there are a number of areas where these games can differ. Here we'll focus on five main areas, explaining concepts, providing examples, and listing some best practices for libraries to consider in each area. These areas are:

- Deeper Strategic and Tactical Decision Making

- Wide Decision Space

- Player Interaction

- Game Mechanisms (Mechanics)

- Narrative Potential (Theme)

Deeper Strategic and Tactical Decision Making

In the world of designer board games, two camps firmly arise - one camp focuses on strategy deep thinking and one focuses on tactics and fast mental reflexes, with many games providing a healthy dose of both.

For example, in the popular tile-laying game Carcassonne, the strategic element is to decide which potential paths to victory is a player going to take - is she going to build large cities, focus on farms and/or roads? Even more broadly, does she plan on playing a defensive game, attempting to build her own large cities/road/farms or play an offensive game and attempt to block other players from building? The tactical elements come from the random tiles drawn each round. As the game board changes, the players will have to make quick decisions in order to solve smaller, more pressing problems. This game can have strategy for the entire game as well as tactical thinking every turn.

In a game like 1775: Rebellion, a simple wargame set at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, players need to align themselves with a strategy first and then most tactical decisions, in this case small skirmishes and battles, are determined for them through dice rolls. In a game like Dixit, a light, fun storytelling game, there is no overarching strategy at all! Players need to make new decisions each turn depending upon what card is played and what story is developed. An even better example is the Push Your Luck game, Incan Gold, where players make the tactical decision when to move further into an ancient temple chock full of treasure and traps and when to get out and deposit their treasure back at their home camp (and thus ensuring them points for the end of the game). The tactical element of Incan Gold is that the cards played to represent the temple are constantly changing so any long-term strategy is difficult and players need to think on their feet.

As a general rule, tactics are quicker to learn and recognize and thus tactical games are better for new and emerging gamers. However, tactical games can bore experienced gamers who desire deeper strategy.

Best Practice for Libraries

Provide a wide array of both strategic and tactical games. It is very likely your patrons will not be able to identify which they prefer. By playing games that span the gamut you will be able to pinpoint games which your patrons prefer.

Try these games for strategy:

Try these games for tactics:

Wide Decision Space

Wide Decision Space

Another attribute of designer board games is a wide decision space. Simply put, these board games provide players with many options during their turn. A wide decision space makes the game a rich, engaging, and mentally chewy experience. However, a wide variety of options can easily overwhelm and intimidate new players causing stress and frustration. As the decision space grows in a game, the options for the player will increase as well as the amount of information to process. This will also make teaching the game more challenging for the moderator as all possible combinations may need to be explained.

For example, in my library gaming group, I was increasing the complexity session by session in a particular type of game my group enjoyed - worker placement games (games where you place "workers" or game pieces to gain resources or actions. Again, I will delve into types of games in a later post). I started with a gateway game called Stone Age where most of the possible decisions were obvious from the layout of the board. A player can gather food, wood, clay, ore or gold; they can collect sets of cards or perform a few other actions.

It was a huge hit and my players wanted more so I provided similar games (such as Lords of Waterdeep or The Manhattan Project) and increased the complexity until I hit a game called Troyes. The game had a much larger decision space than previous games and was difficult to teach, slow to play and, overall was not enjoyed as much due to the growth of overwhelming options. There were so many and they tended to change throughout the game! Games similar to Troyes such as Trajan or Caylus are wonderfully complex and deep games but I don’t recommended you start with them. They were simply too heavy.

- A light game has a small decision space and will be appropriate for beginners.

- A medium game will have a larger but probably static (not changing throughout the game) decision space and would be appropriate but will require teaching and moderation for beginners.

- A heavy game has a robust decision space with options that potentially change over the span of the game.

The "weight" of a game is not solely determined just by decision space. Other factors include length and amount of rules, play time, amount of long term strategy vs. luck/chance, atmosphere and accessibility of theme. All these facets affect how easy or hard a game will be to teach, learn and play. We will examine each of these in a future post and provide some game examples that exemplify each category.

Best Practice for Libraries

Be aware of the decision space in a game. How many options will a new player have to learn? If you are teaching a game, find something with a small decision space and then grow into games with more options. If the target audience is experienced then go for a larger decision space.

Try these games for a small decision space:

Try these for a larger, but still

manageable, decision space:

Player Interaction

Player Interaction

Player interaction is a deep topic and for me the core of why I play games - to interact and enjoy time with other people. Different games encourage different types of interactions between players, create varying amounts of noise, and require different levels of attention.

Games can be cooperative, where all players are working together in order to win, they can center around direct competition and conflict and they can involve teams or hidden betrayers! However, across the board (Ha!) all board games have some level of social interaction inherent in the gameplay. Finding what level of social interaction is appropriate for your group and your library is important.

For example, the tempo of Escape: The Curse of the Temple - a fast, tense cooperative game - will generate plenty of loud, boisterous player interaction. Games such as Dominion, Sushi Go! or 7 Wonders (all card drafting games) will tend to be quiet and somber.

A balance between these two elements needs to be struck so when considering whether to choose a game for a library gaming group it is important to take into consideration the space and proximity towards other patrons and the type of interaction the game may produce (and thus level of table-talk and noise).

Best Practice for Libraries

Know your space and how much noise is appropriate to the culture of your library. Don't be afraid to make a little bit of noise though. The best way to attract a crowd and encourage new gamers is to have fun and to look like you are having fun! Try to avoid any game that includes player elimination. The best way to encourage a new group is to introduce cooperative play.

A few games which create a sense of cooperation and help draw a crowd are:

Game Mechanisms (Mechanics) and Narrative Potential (Theme)

In the world of designer board games there is a constant tug-of-war between the theme of the game (the story, setting, subject and character of a game) versus the mechanisms (the internal machinations "moving parts" of the game, the rules, how the games is played, elements of gameplay etc.).

In the world of designer board games there is a constant tug-of-war between the theme of the game (the story, setting, subject and character of a game) versus the mechanisms (the internal machinations "moving parts" of the game, the rules, how the games is played, elements of gameplay etc.).

With a heavily thematic game, the game play will be immersive and robust: Similar to a choose-your-own adventure book you will feel as if your actions have relevance to the growing story within the game. If you are a firefighter or a colonial marine you will feel like a firefighter or a colonial marine. Story arcs and the context of the game will be integral to the experience of theme.

A game with a focus on mechanisms may be complex and deep or elegant and fluid but the focus will be more on what you are doing rather than the story surrounding those actions. Common board game themes and mechanisms will be the focus of a future post - stay tuned!

The marrying of theme and mechanisms can be difficult but one game does it particularly well - Letters from Whitechapel.

In this game, one player plays Jack the Ripper and the rest of the players play investigators searching for Jack as he chooses and dispatches victims (dark, immersive theme!). The main (and really only) mechanism in this game is "hidden movement" where Jack moves about the board while the investigators try to pinpoint his location. They don't know where Jack is, but Jack can see where the investigators are located and what they are planning. This makes for an increasingly tense game for Jack as he can tell when he is getting cornered and trapped by the investigators. For the investigators, not having all the information needed to locate Jack can be an incredibly frustrating experience. This blends together to create a tense, delicate, and fast-paced game of cat and mouse.

Best Practice for Libraries

Find games which blend theme and mechanics well - games which provide a narrative along with solid, fluid gameplay. This is subjective and difficult to provide a definite list of good games. The best bet is to explore both theme-driven games and mechanic-driven games with the gaming group. Chances are they will be split 50/50.

Stay tuned, there is more to come!

I hope this provided some information to get you started. Keep in mind that while designer board games have the benefits of increased tactical and strategic opportunities, a wider-decision space, increased narrative potential, and richer game experiences compared to mass-market games, it does come with a cost.

As games become more innovative and complex the rules become more complicated and the game play more intricate. The games are of a higher quality but also have limited print runs, go out of print quicker, and can cost more than mass-market games. Patrons whose internal template for games are the simple, single-mechanic games of their childhood will require some help navigating this new world.

After this brief introduction, future posts will examine the topics of:

- theme and mechanics

- player interaction

- depth of strategy

- the care and feeding of a board game group

- marketing, collection development and generating buy-in

Libraries can thrive within the space of board gaming as much as (if not mor than) the video game space they already thrive in.

John Pappas is the Library Branch Director at the Primos Branch of the Upper Darby Township / Sellers Free Public Library. He enjoys talking about emerging technologies, gaming, public librarianship, outreach, and zen.