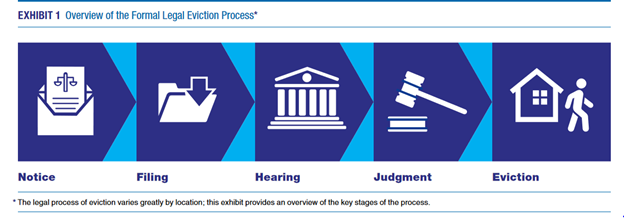

Five Phases of Eviction

![]()

This information on the Five Phases of Eviction is also available as a PDF to download.

Eviction is defined as the forceful expulsion of a tenant from a rental property. This process may be resolved formally through the civil legal system or informally between the landlord and tenant(s) with no legal processes involved. Nonpayment of rent is the most common reason for eviction, although lease violations, property damage, criminal activity, and other issues can also be cause for initiating eviction proceedings.

The graphic below outlines key phases in the eviction process. Since the process of eviction is determined by state, county, or local laws, the steps that follow an eviction filing may vary drastically from one jurisdiction to the next. The specific local actions taken by tenants and landlords during the eviction process can be critical in determining the final outcome. Waiting periods must be observed. The appropriate forms and fees must be submitted. Timely appearance in court is required. All of these steps must be followed according to the rules and procedures of the court. Failure in any of these areas can mean the difference between winning and losing a case.

Phase 1 - NOTICE: Initiation of eviction - The landlord usually notifies the tenant in advance of the intent to file eviction. The amount of time may vary by state and by circumstance, e.g. failure to pay rent vs. engaging in violent criminal behavior. The cause for the eviction and the next steps in the process must be outlined in the notice. Some locales specify what information should be included in an eviction notice and provide detailed requirements for its delivery; others do not. If the notice does not include specific information about next steps to take, tenants can seek help from legal aid organizations or self-help resources through the courts. In some states, tenants are required to respond to a notice. If they do not respond, a default judgement can be given in favor of the landlord.

Phase 2 – FILING: After the notice is given of the intent to file, time passes in which the tenant may be able to address the issues prompting the landlord to seek eviction – for example, by paying back the rent owed or correcting a violation of the lease terms. If the tenant does not take the corrective action indicated in the notice, then the landlord can take the next step and file to have a hearing with the court. The landlord pays a filing fee (higher fees may deter landlords). Once filed, it becomes public record and may affect the renter’s credit rating and ability to find future housing. For this reason, stopping the process at or before the filing phase protects renters on both a short and long-term basis. Where an eviction case is first heard varies by state. In some states, cases are heard in county courts and each county makes its own rules, e.g. how much landlords are charged to file or initiate an eviction action.

Phase 3 - HEARING: The court process - Once a landlord files an eviction case, the tenant will receive a summons to appear in court for a hearing. It is important for a tenant to show up to the hearing; if they do not, a default judgement can be given in favor of the landlord. When tenants come to court, they have a legal right to mount a defense. The types of defense that are allowed are defined by the jurisdiction; for example, in Louisiana it's unlawful to evict someone because of a domestic violence incident, but the victim has to provide "reasonable documentation" of the abuse. Defenses like this aren't available in all jurisdictions, or sometimes come with very complicated requirements that make it difficult to use.

Phase 4 - JUDGMENT: The judge makes a ruling - In many jurisdictions, a ruling in favor of the plaintiff (landlord) is by far the most common outcome of an eviction case. If a judge rules in favor of the landlord, the tenant has a certain number of days (varying by locale) to vacate all possessions from the rental property. There may be an option to appeal the decision, but in most states/territories, tenants will have to pay some amount of money to the court in order to appeal. That can often make the ability to appeal out of reach.

Phase 5 - EVICTION: Post-hearing - If the tenant loses, they have a certain number of days to vacate. If the tenant doesn’t vacate, the landlord can file a writ of possession with the court and pay an additional fee to regain control of the property. A writ of possession (also called a writ of eviction) is issued after a landlord wins an eviction case in court. This order allows a landlord (person or group) to take possession of real property by forcing the tenant currently in possession of the property out. If the tenant does not vacate, law enforcement officials can remove the tenant and their possessions. When eviction cases result in a ruling or default judgment against the tenant, they may be required to pay court and attorney’s fees in addition to back rent owed, late fees, and other monetary penalties. Some jurisdictions do not require additional notice to be given before removal occurs. Additionally, some jurisdictions have an abandoned property statute requiring landlords to store any property left behind by tenants and formally notify them of how to collect their belongings.

Sources:

- A Common Story: The Eviction Process in Shelby County, TN

- On the Brink of Eviction: Trends in Filings under State and Federal Moratoria

This eviction resource is part of the Improving Access to Civil Legal Justice initiative. In partnership with the Legal Services Corporation, WebJunction provides resources that focus on strengthening library staff’s ability to respond to eviction questions with confidence and close the justice gap in their communities. oc.lc/eviction-resources

Learn more about libraries and Civil Legal Justice

- Creating Pathways to Civil Legal Justice, a free self-paced course series available in WebJunction’s Course Catalog, exploring how public libraries can help to address the justice gap. Learn more about the course series, including a short video, in this announcement.

- Find additional resources related to libraries and legal services: oc.lc/legal-justice